by Sheikh Nuh Keller

Dala’il al-Khayrat, the most celebrated manual of Blessings on the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace) in history, was composed by the Sufi, wali, Muslim scholar of prophetic descent, and baraka of Marrakesh Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli (d. 870/1465). Born and raised among the Gazulah Berbers of the Sus region in southern Morocco, he studied the Qur’an and traditional Islamic knowledge before travelling to Fez, where he memorized the four-volume Mudawwana of Imam Malik and met scholars of his time such as Ahmad Zarruq, and Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullah Amghar, who become his sheikh in the tariqa or Sufi path.

Amghar traced his spiritual lineage through only six masters to the great founder of their order Abul Hasan al-Shadhili and thence back to the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace). After initiating Jazuli into the way, he placed him in a khalwa or solitary retreat, where he remained invoking Allah for some fourteen years, and emerged tremendously changed. After a sojourn in the east and performing hajj, Jazuli himself was given permission to guide disciples as a sheikh of the tariqa.

Imam Ahmad al-Sawi relates that one day Jazuli went to perform his ablutions for the prescribed prayer from a nearby well but could not find any means to draw the water up. While thus perplexed, he was seen by a young girl who called out from high above, “You’re the one people praise so much, and you can’t even figure out how to get water out of a well?” So she came down and spat into the water, which welled up until it overflowed and spilled across the ground. Jazuli made his ablutions, and then turned to her and said, “I adjure you to tell me how you reached this rank.” She said, “By saying the Blessings upon him whom beasts lovingly followed as he walked through the wilds (Allah bless him and give him peace).” Jazuli thereupon vowed to compose the book of Blessings on the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace) which came to be known as his Dala’il al Khayrat or “Waymarks of Benefits.”

His spiritual path drew thousands of disciples who, aided by the popularity of his manual of Blessings on the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace), had a tremendous effect on Moroccan society. He taught followers the Blessings upon the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace), extinction of self in the love of Allah and His messenger, visiting the awliya or saints, disclaiming any strength or power, and total reliance upon Allah. He was told by the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace) in a dream, “I am the splendor of the prophetic messengers, and you are the splendor of the awliya.”Many divine signs were vouchsafed to him, none more wondrous or unmistakable than the reception that met his famous work.

Its celebrity swept the Islamic World from North Africa to Indonesia. Scarcely a well-to-do home was without one, princes exchanged magnificently embellished copies of it, commoners treasured it. Pilgrims wore it at their side on the way to hajj, and a whole industry of hand-copyists sprang up in Mecca and Medina that throve for centuries. Everyone who read it found that baraka descended wherever it was recited, in accordance with the Divine command: “Verily Allah and His angels bless the Prophet: O you who believe, bless him and pray him peace” (Qur’an 33:56).

In the post-caliphal period of the present day, Imam Jazuli’s masterpiece has been eclipsed by the despiritualization of Islam by “reformers” who have affected all but the most traditional of Muslims. As the Moroccan hadith scholar ‘Abdullah al-Talidi wrote of the Dala’il al-Khayrat: “Millions of Muslims from East to West tried it and found its good, its baraka, and its benefit for centuries and over generations, and witnessed its unbelievable spiritual blessings and light. Muslims avidly recited it, alone and in groups, in homes and mosques, utterly spending themselves in the Blessings on the Most Beloved and praising him—until Wahhabi ideas came to spread among them, suborning them and creating confused fears based on the opinions of Ibn Taymiya and the reviver of his path Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab of Najd. After this, Muslims slackened from reciting the Dala’il alKhayrat, falling away from the Blessings upon the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace) in particular, and from the remembrance of Allah in general” (alMutrib fi awliya’ al-Maghrib, 143–44).

A New Dala’il al-Khayrat

It was our hope that Allah might turn this tide by helping us bring forth a new edition of Jazuli’s famous manual that would be more beautiful, accurate, and easy for Muslims to use than any previous printing.

The Text

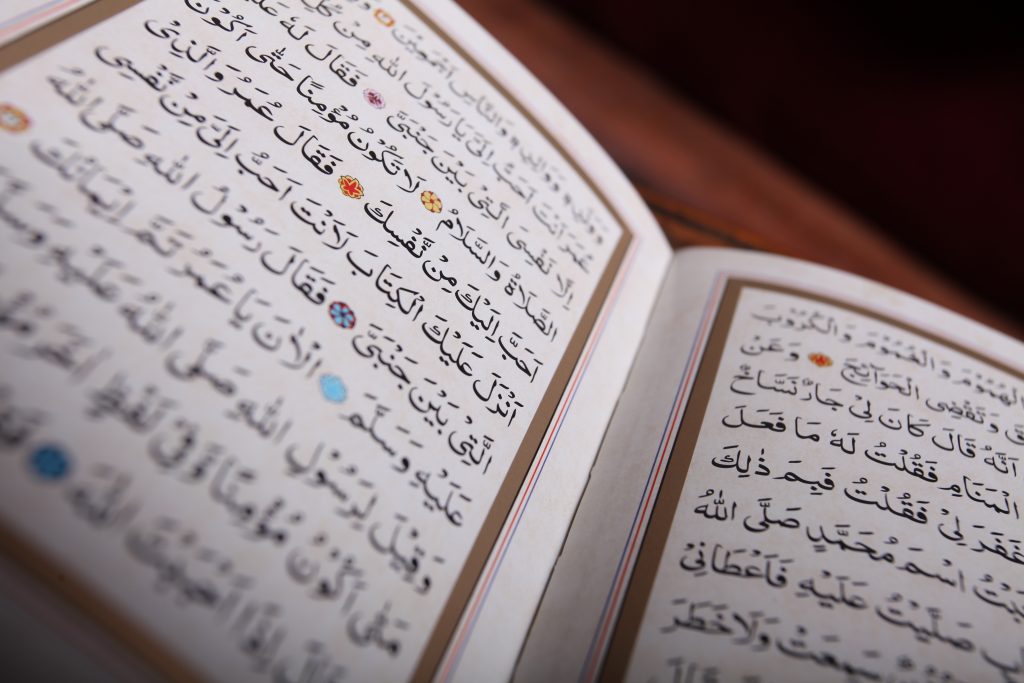

We began in June 2003 with a survey of ninety-five manuscripts of the Dala’il from several countries. Their minor textual variants led us back to the work’s excellent and detailed commentary Matali‘ al-masarrat by Imam Muhammad Mahdi al-Fasi (d. 1109/1698), not the least because of his exhaustive comparisons of major early copies, particularly the Sahliyya recension, read with Jazuli seven years before his death by his disciple Muhammad al-Sughayyir al-Sahli and widely acknowledged as the most authoritative. Perhaps no author can resist a few changes in his work when read aloud to him, and differences between the earliest sources are probably due to this. The Sahliyya however enjoys the greatest celebrity of those copies actually checked with the author, and our edition follows it almost without exception.

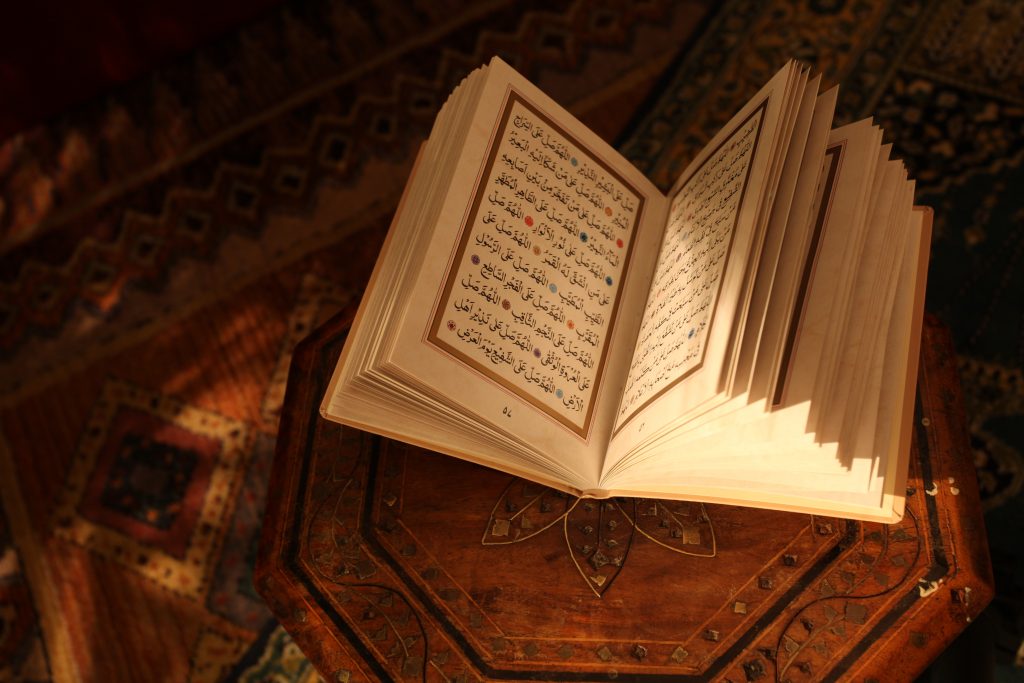

By careful comparison of manuscripts and commentaries, we corrected the traditional chapter headings and subtitles, dividing the work into the customary daily portions of halves, thirds, quarters, and eighths or hizbs or “sections.” The practice of naming the hizbs according to the days of the week proved unattested by the earliest sources, and even less probable since they number eight, not seven as do the days of the week. (Two sections are read on the last day of the week.) From beginning to end, we placed the ornaments traditionally used to mark pauses in the recital, based on the rhythm, rhyme, length, and meaning of the phrases.

The Calligraphy

We searched in Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Morocco for a calligrapher whose Arabic script could best reflect the beauty, light, and wilaya of the work, while being easy to read. The samples we saw of the naskh script normally used in Arabic handwritten books led us to the Syrian master Uthman Taha, one of the most familiar calligraphers to contemporary Muslims for having written the pages of the Saudi Printing of the Holy Qur’an found in mosques throughout the world. We visited him at home in Medina and found him a man of sincerity and din, who had written out the entire Qur’an twelve times. He produced the 182 large-scale pages of the work—fifty-two by thirty-four centimeters each— in just three months.

The Illumination

We contacted the Turkish artist Necati Sancaktutan to draw the ornaments used for the pauses in the text, and then an Iraqi team of two brothers, Muthanna and Muhammad al-‘Ubaydi, to produce the illumination for the sections, beginnings, and end. They came to Jordan twice, on their first visit providing samples and discussing color and style, and on their second bringing their tools, colors, and gold for the main work, which they completed in approximately fifty days.

Their work was beautiful, but required high-resolution scanning, cleanup, and conversion into digital “pathways” to allow us to electronically color it for printing. Ibrahim Batchelder, an American craftsman specialized in Islamic fine arts and design, helped us with this and many other matters connected with the ornamentation.

The Hadiths

We wanted to clarify to readers the hadiths in a prefatory chapter to the main work that were not authenticated of the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace), so we produced a detailed report on every hadith in the section, edited it

for brevity, and sent it to Uthman Taha to write out for inclusion at the back of the work.

The Ijaza

For the baraka, we also wanted to add a sanad or chain of transmission of the ijaza or spiritual authorization to recite the Dala’il, as we had for our previous Awrad alTariqa al-Shadhiliyya [Litanies of the Shadhili Order]. We already possessed personal ijazas for the Dala’il from the late Sheikh Muhammad ‘Alawi al-Maliki of Mecca (Allah have mercy on him) and Habib Mashhur bin Hafidh of Hadramawt, but now sought a higher sanad, meaning one with fewer intermediate links, back to the author. After some weeks, we received the ijaza of the former Queen of Libya, Fatima Shifa’ (may Allah preserve her), who relates the work through the Sanusiyya of Libya back to Imam Jazuli. Upon her authorization, we wrote out an ijaza for readers, forwarded it to the calligrapher, and when it was finished, scanned it and added it to the rest of the work.

The Design

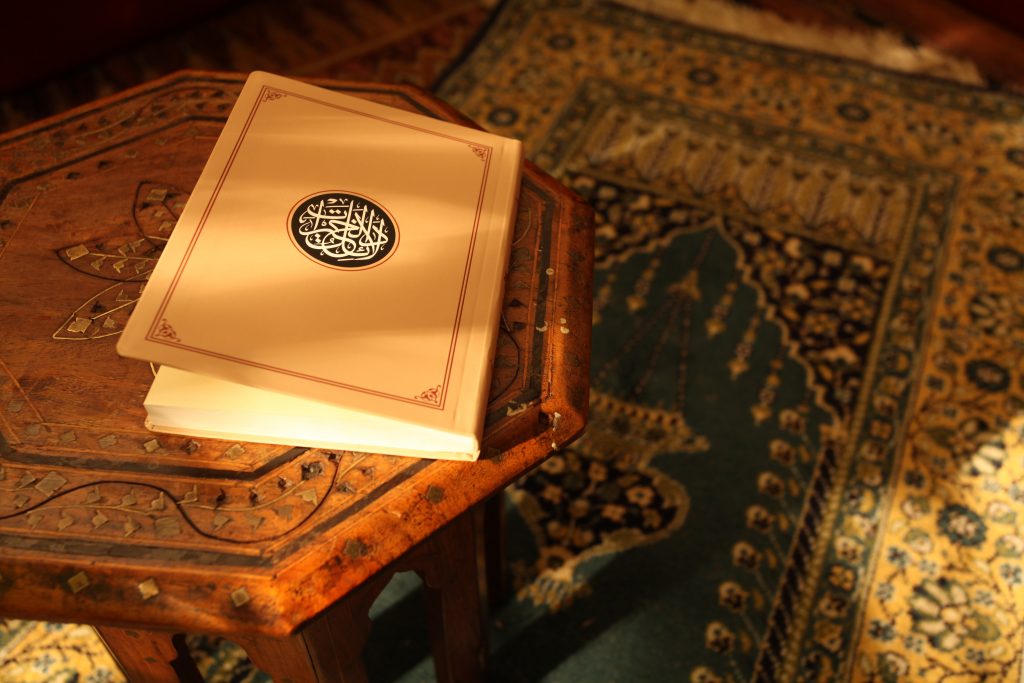

The book’s size, page layout, frames, gold, and colors were designed to match traditional handwritten copies of the Dala’il al-Khayrat from the Near East. The work remained without page numbers because none of the older copies had them, and section titles rendered them largely superfluous. Too, the pages of the Dala’il, like many handwritten copies of the Qur’an and indeed most Islamic manuscripts, were traditionally collated and ordered not with numbers but by using the ta‘qiba system of copying the first word of the left-hand page at the bottom of the righthand page. We followed this system, and also the traditional way of handwriting corrections in the margins and indicating their place in the text with a small pen stroke.

Finally, we commissioned the Iraqi calligrapher ‘Abbas al-Baghdadi to produce the circular medallion of the book’s name that graces the cover and the first page of the work.

The Printing

After many steps to prepare the materials, we printed the work at National Press in Jordan. They were recommended by their proven excellence in color work in previous art calendars and other projects, and by being able to produce a sufficiently opulent imitation of the gold used in the original ornamentation. Our typesetter and computer graphics artist Sohail Nakhooda assured us that he could get the best cooperation out of the staff there in the final steps of combining the many electronic elements of each page.

We bound a few hundred copies in Jordan, but then met with Fu’ad al-Ba‘ayno in Beirut, the largest bookbinder in the Middle East, to see his samples and agree upon the materials to be used for both the rest of the printing, and the deluxe limited edition, with its special handmade oak presentation boxes. Everything was finished by July 2005, twenty-five months after we began, and may Allah be praised.

A Note of Thanks

All thanks to our Maker for everything to do with this work. We would also like to express our gratitude to those of His servants who helped us with it, whether with little or much. A special thanks is due to Iyad al-Ghawj, who helped with the text and oversaw the calligraphy and ornamentation; Sohail Nakhooda for his invaluable technical assistance and electronic editing; Ibrahim Batchelder, whose help and advice did so much to illuminate the work; Ahmad Snobar, who checked the text and its pauses; Muhammad Isa Waley for showing us copies and photographing many pages and covers from the Manuscript Collection of the British Library; and to all those whose love of the Holy Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace) and prayers and help made it possible to produce Jazuli’s enduring masterpiece in this new raiment.

May Allah reward with paradise everyone who had a hand in it, and bless our liegelord the Prophet Muhammad (Allah bless him and give him peace) in the measure of every prayer, word, and letter recited of the Dala’il al-Khayrat until the end of time.

Nuh Keller, Amman, Jordan.

This was written by Sheikh Nuh Keller in 2005 when the first printed edition was released.